As I implied in my last positing, not all fingerings on the printed edition in front of you are meant to make the learning of the piece easier (technical fingerings). Some bear very specific phrasing implications. Now..those of you who have been reading my past few posts know that I advocate finding your own way to interpret music, and have your considerations and relationships to the notes be present in performance. What I am going to advocate today is to have a look at these "phrase fingerings", and find out what we can learn. This is especially true with markings found in Segovia's editions of works. Many of his fingerings directly imply a phrasing point of view and should be considered.

"But why, Dr. Steve? I'm an individual, I'm special, my girlfriend finds my musical sensibilities impeccable, etc...." I hear this a lot from students (or some variant thereof).

My answer usually boils down to tradition. When I was in my early twenties, it was very much in vogue for students to eschew fingerings, especially those of Segovia's. We viewed them as old-fashioned, belonging to a style that was past and perhaps a bit too much "heart on the sleeve." Perhaps I studied too much post-modern theory in college, but in recent years, I no longer buy into the view that music history is a progress narrative - a timeline in which Beethoven improved upon the style Mozart, Berlioz improved the language and instrumentation of Beethoven, and Wagner improved upon the notion of tonality previous to him - a notion that older books on the subject suggest, and theory books definitely do. Segovia's interpretations may belong to his time, but its a part of our instrument, arguably one of the more important aspects of it as well. Segovia captured the minds and hearts of music lovers for decades and continues to be the guitar's most recognizable voice. We have heard hundreds of others play the Segovia repertoire, but why is Segovia's presentation of this music what we always reference (in either a good or bad manner)? Surely on this fact alone, we are obliged to look at and consider his musical approach when offered to us. I will never advocate always using these fingerings, but they are a involved in a very successful part of the history of the instrument and show us invaluable revelations into the classical guitar's aural history.

How do we know fingerings are for phrasing and not for technical purposes? There is not a simple answer for this, and many fingerings have implications for both. For me, however, there is one style of fingering that seems to always have phrasing implications, and is summed up in the subtitle for this post. Swinging Singles!! This could be Single String or Single Finger, but the impractical use of a solitary technical point of view is usually an indicator. Fingerings of this type for phrasing embody two gestures.

1) A consistency of timbre (Left Hand and Right Hand technique)

2) A gesture which displays the physicality of a musical line (the rising and falling of line, the leaps up or down to wider intervals)

Right Hand Fingerings for Phrasing

A lot of time in the practice room, is spent trying to find consistency of tone and rhythm amongst all of our right hand fingerings. Therefore, in theory, there would probably not be to many right hand fingerings written in to an edition that would have phrasing applications. Once I accepted this, I found almost no fingerings which implied phrasing based upon the two tenets of "phrase fingerings" I stated above. For example, if an editor has stated that you must use i m alternation for a passage, there is no reason that a person very skilled in i a alternation shouldn't be able to produce the same effect.

So, I've now proven that all Right Hand Fingerings on an edition either facilitate learning or show the editor's technical bias (see last post).....EXCEPT.....

Have you ever seen videos of Julian Bream or other great artists play? One of the most effective techniques for timbral control is the use of a single right hand finger repeatedly for a single musical line. I have looked through a number of editions to give evidence of this to you, but unfortunately, I have nothing at my house at the moment that would serve this purpose. If I do find something, I will be sure to post it immediately. I've seen this most commonly employed in contrapuntal Bach works. Especially for a fugue exposition, it can be an excellent way of controlling the dynamics and tone of a line, for a line that merits this type of musical control. Philosophies on phrasing in the works of Bach differ wildly from player to player, and this is a topic I will bravely delve into in a later post, but experimenting with this single finger approach can aid a player in developing seperation between voices and phrasing independence.

The issue if Right Hand fingerings for phrasing is complicated. In my experience, most of these fingerings printed in a score do reveal a technical approach. While the editor may argue that the use of certain fingerings reveals an intended phrasing, it would be hard to argue that they don't reveal the technical bias of the editor in how

they apply it to phrasing. Again, my advice is try them out, but allow your aesthetic to be the one that guides you if you feel a certain right hand approach would suit the musical effect you wish to bring out.

Left Hand Fingerings for Phrasing

In determining if a left hand fingering is designed to illustrate phrasing, I start from a technical standpoint. If I am looking at a printed score, and I suddenly say "Why the @#$%& would I do that when I could do this more comfortably?" then what I am confronted with is usually something that has phrasing implications. It is important to identify these fingerings in the score. I usually use a three step process to determine a L.H. "phrasing fingering"

1) Is this fingering characterized by a certain awkwardness? (Shifting or squeezing of the hand usually)

2) Is there a timbral consistency to this fingering? (usually characterized by shifting on a single string or set of strings)

3) Is the physicality of the line expressed? -(for example, if there is a wide intervallic leap, does the fingering make me exert an effort to execute this leap)

Question 1 usually implies a "phrasing fingering" if answered yes. BUT..while many awkward fingerings are "phrasing fingerings", not all phrasing fingerings are awkward. Questions 2 or 3 usually indicate an approach to phrasing or contour, and may or may not involve awkwardness.

As I mentioned above, one of the great resources for us as members of the classical guitar heritage and tradition, are the editions of Andres Segovia. While often lighter in Right Hand markings, there can usually be found an abundance of Left Hand markings that allow us an insight into the technical and musical approaches of the Maestro (One notable exception being Milhaud's

Segoviana which bears no markings at all). Recently, a number of students of mine have been playing Ponce's

Sonatina Meridional. Often times, they come in with a more convenient technical approach to gestures than the ones Segovia suggests. At this point, I take them through the Segovia fingerings in certain passages to illustrate these concepts of phrasing in the left hand. Incidentally, I also have a copy of Tilman Hoppstock's excellent urtext edition handy to point out note errors in the Segovia edition, as the use of a C-sharp in measure 29 of the first movement instead of the proper C-natural as Maestro Kassner corrected for me has always grated my ears. But I digress...some examples....

As anyone who has learned the Segovia scales knows (and everyone should have learned them at one point), Segovia placed a great deal of importance on Left-Hand Shifting, and obviously emphasized this in his practice of technique. Other scale systems, such as Carlevaro or Shearer, use less of the horizontal shifting approach than Segovia did, and we can infer that his fingerings in these scales show his wish for students to practice this approach.

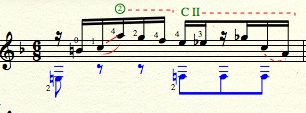

A moderate example from the first movement:

The most obvious feature of this passage is the shift on the first string. A lot of modern guitarists use an open string for the first E to allow time for the shift to fifth position (which is not a bad idea, by the way). Segovia chose to shift along the second string. Why? Did he hate the sound of his open E-string. Well...no...he uses it in the next bar, albeit in a more harmonic way, but it also helps technically for the shift down to second position which follows. So now id do my check:

1) Slightly awkward (shift of three frets quickly)

2)There will be timbral consistency for the opening of the scale passage (first 5 notes on 1 string)

3) No leap intervallically, but shifting in itself is a physical gesture which shows an ascent.

Assessment: While it does show technical preferences of Segovia, there are clear phrasing implications.

A more extreme example for the second movement:

There are obviously more convenient ways to approach this technically. One solution would be to go to Third position on beat 3 and play the A on the first string, then simply stay in third position. Segovia, however, opted for a heroic leap up the neck with a (partial) portamento as an added effect. Romantic early twentieth century performance practice at its most apparent. Lets put it through the criteria check:

1) Indeed awkward! (Shift of six frets)

2) Melody stays on the second string for most of the measure. Timbral consistency.

3) The act of shifting so far up the neck displays a physical manifestation of the leap of a major sixth.

Assesment: Definitely a fingering that expresses an approach to the performers approach to the musical affect.

An extreme example from the third movement:

This is always the excerpt that opens up the discussion about Segovia phrasing and technique with my students. This "squirel-ly" little fingering is tough to pull off at a fast tempo and demands enormous control of both hands to execute well. Now to the test:

1) Very awkward (shifts up and down in very quick succession, including a quick one on the 4th finger followed by a triplet slur. There are at least three more convenient fingerings I can see without putting too much effort into thinking about it)

2) Timbral consistency. Its all on the third string

3) Displays physicality in that this quick little figure can appear virtuosic if executed in this fingering

Assessment: Phrasing implication explicitly! Again, there are many ways to play this in a technically simpler manner, but the aural effect of playing it in Segovia's manner is unique and uniquely expressive.

So...do we use them. As stated earlier, the tradition in art music is important, as is our more immediate history of performance on the guitar. I would no longer eschew this fingering outright. We can learn a lot about not only Segovia, but the musical environment he was operating withing by learning his fingerings in these phrasing situations. As a performer, I am more inclined to use a Segovia (or any other performer's) fingerings if they express a musical point of view. The technical fingerings are still very subjective to me. The phrasing fingerings, while still being subjective, do help us learn our art (as opposed to craft) in a very meaningful way that allows our reverence for the tradition. That's not to say that one should always use them. After living with a piece, you must decide whether these appraoched are consistent with your style, or your communication with the piece. To summarize, I would learn them, but keep in mind WHY you have learned them, and make your decisions as your relationship to the music develops.

Fingerings on Printed Editions: Summary

I've discussed a lot of concepts in the past two posts, so I'll proved a brief summary about my thoughts on this subject.

Right Hand Fingering

-usually displays the technical bias of the editor. Rarely (if ever) is the only way to execute the passage. In pedagogical works, try and understand the technical reasons for the fingering, and assimilate those technical efforts into your playing. In concert works, acknowledge the technical standpoint of the editor but always strive to use only what will allow you the fluency to execute. If an editor's fingering doesn't work and you have a more comfortable solution, use yours. Rarely will this decision affect the musical outcome of your performance.

-there are not to many instances of R.H. fingering that influence the music from purely a phrasing standpoint. Look for unnatural uses of repeated single fingers - they provide you with an interesting option.

Left Hand Fingering

Remember the two categories of left hand fingering that facilitate the technical learning of the piece

1) The Absolute Positively Only Way to Do Something (probably...) - these will help speed up the learning process and don't involve the editor's technical bias

2) Fingerings that will help you learn the piece - Subjective, reveals some of the editors approach to technique.Try it out first, but feel free to search out alternatives based upon personal technical and musical concerns

To determine if a fingering has phrasing implications, look for a certain amount of unnecessary awkwardness as a clue to its existence and then ask yourself these 3 questions:

1) Is this fingering characterized by a certain awkwardness? (Well ask it again..you may as well)

2) Is there a timbral consistency to this fingering?

3) Is the physicality of the line expressed?

If at least two of these are answered "yes" you may be looking at something that a considerable artist has concerned important for your attention, and we should honour that artist by attempting to understand it.

Keep practicing!!

S